Natural disasters and their terrible impact on human societies have almost gone full circle.

In the past, slow communication and the technical inability to monitor extreme weather meant that we rarely heard about disasters in far-away lands. Then came T.V. news, overwhelming us with heartbreaking coverage about natural disasters causing unfathomable damage to the developing world.

Now, as the poor have gotten richer and the spread of affordable technology has allowed warning systems and protective measures to be put in place, we no longer hear about disasters killing hundreds of thousands of people – simply because that horrific destruction rarely happens.

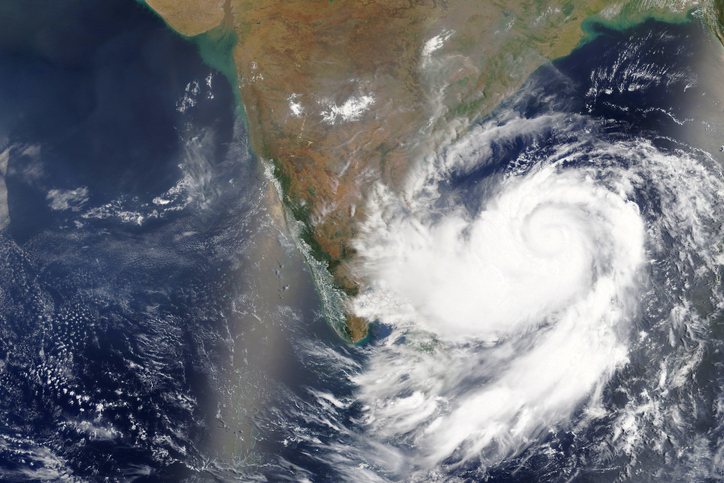

Take Amphan, the Super Cyclone that hit Bangladesh and India’s Northeast in May last year. Even though it was one of the strongest cyclones ever recorded and the damages made it the most expensive storm to hit the region, you probably haven’t heard about it. Why? It killed a grand total of… 128 people. The ideal number of deaths is zero, but it’s still a remarkable achievement for humankind that the death toll was so low.

Consider what the figure could have been. Last year, we also saw the 50th anniversary of Cyclone Bhola. In November of 1970, what by all metrics was a physically weaker cyclone than Amphan, Bhola killed more than 300 thousand people in Bangladesh alone. Because of human progress, we don’t see fatalities that high anymore.

A World Health Organization bulletin lists some of the many contributing factors to the decline in extreme weather deaths, which have “been achieved by modernizing early warning systems, developing shelters and evacuation plans, constructing coastal embankments, maintaining and improving coastal forest cover and raising awareness at the community level.”

The accurate forecast of weather and flood risk in May 2020 allowed the Bangladeshi people – inside and outside of government institutions – to prepare. A full three days before impact, meteorological offices issued clear and wide-ranging warnings on every platform available to them. These warnings allowed millions of people to move away from harm’s way, move boats and equipment up the rivers to comparative safety, stock up on necessities, and prepare freight of humanitarian aid from abroad.

None of these improvements can happen without money, stable and responsive governments, and advances in technology to protect and warn against oncoming storms. Already in 2015, the Bangladeshi statistics bureau reported that about two-thirds of households got early warnings for approaching cyclones and floods, and between 75 percent and 90 percent of households were prepared for the most damaging disasters.

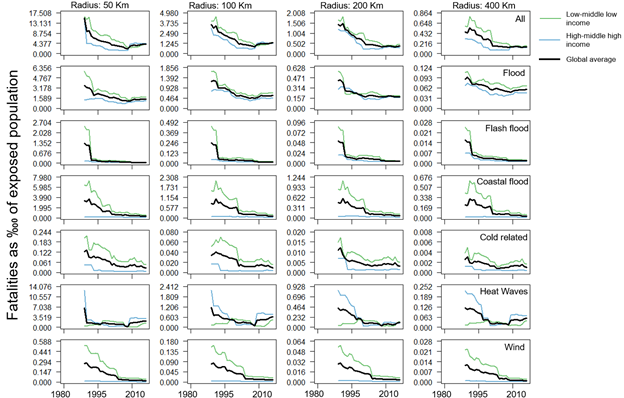

The amazing fall in Bangladeshi deaths from natural disasters over the last half-century shows how technology and human adaptation can deal with an unruly nature. But this Bangladeshi wonder is not unique. Disaster-related deaths are falling in other countries and even globally. In the scientific journal Global Environmental Change, Giuseppe Formetta and Luc Feyen investigated damages and deaths from natural disasters in low- and middle-income countries. They found that across different geographic regions and for all major categories of natural disasters, fatalities in poorer countries have fallen dramatically and are almost on par with rich countries.

Source: Giuseppe Formetta and Luc Feyen

The authors’ conclusion goes against what most climate headlines would lead us to believe:

“From 1980–1989 to 2007–2016, the 10-year moving average mortality rate, averaged over all hazards, radii and both income groups, has reduced more than 6-fold, while the economic loss rate dropped by nearly five times. […] vulnerability converges between lower and higher income countries due to the stronger vulnerability reduction in less developed countries.”

Economic and political freedoms and technological advances play large and often unseen roles in human progress. Take Bangladesh’s neighbor Myanmar, which is one of the least free countries on the planet. The country shares many of the same geographic vulnerabilities that Bangladesh and Northeast India do but suffers much more. For example, in 2008, Cyclone Nargis killed an estimated 150,000 people in Myanmar, while a cyclone of similar magnitude hit the much-better prepared Bangladesh the year before, causing “only” around 4,200 deaths.

Tufts University professor Gregory Gottlieb, a former humanitarian aid worker in Myanmar, writes that “not only did the country lack a weather radar network that could predict cyclones, it also had no early warning system, storm shelters or evacuation plans.” In other words, freedom, higher incomes, preparation, and technological advances matter.

There is a lesson here that’s relevant to the climate change conversations that often dominate the news cycle: no matter what effect a changing climate may have on natural disasters, humans have it in their power to prepare, protect, and adapt to the dreadful power of nature. The difference between a catastrophe with hundreds of thousands of dead and merely a costly clean-up isn’t a degree or two in global average temperature. Rather, it is poverty and venal governments that don’t care about the welfare of the populace.

While we cannot control nature, we can tend to our vulnerabilities. In fact, that is what many countries have already done, which is why the number of people who die from natural disasters keeps dropping. As the poor grow richer and freer, the trend will only get stronger. One day, perhaps, the Bay of Bengal cyclones will not kill a single person.