Summary: Malaria, a deadly disease caused by parasites transmitted by mosquitoes, has plagued humanity for millennia. However, thanks to scientific and technological innovations, as well as global cooperation, malaria may soon be eradicated. This article explores the history, challenges, and prospects of eradicating humanity’s most ancient enemy.

Timothy C. Winegard’s The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator contains many interesting tidbits. For example, the American historian argues that mosquitoes may have played a role in the extinction of dinosaurs. He also notes that the diseases mosquitos carry have been around long enough to alter human DNA (e.g., the prevalence of sickle cell disease among people of African ancestry). According to Winegard, the mosquito “has ruled the earth for 190 million years and has killed with unremitting potency” some 52 billion people (i.e., more than all wars in history combined).

One of the most interesting passages relates to the so-called “Darien Scheme,” which was the Kingdom of Scotland’s attempt to colonize the Gulf of Darién in what is today’s Panama. The Scots came equipped with a printing press and plenty of woolen socks but no earthly idea how to deal with gazillions of mosquitos that promptly wiped the colonists out. The financial hit to the Kingdom was so severe that the Scotts agreed to join forces with the English, thus forming what is today the United Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales) and Northern Ireland.

Malaria, the most common disease spread by the mosquito, is a thing of the past in much of the developed world, but the parasite still infects some 200 million people a year – killing 400,000. Children aged under the age of five are most susceptible to malaria, accounting for a majority of the fatalities worldwide. In addition to the human suffering, malaria imposes huge economic costs on some of the poorest countries in the world – nine percent of the gross domestic product in Chad, for example.

Mercifully, our most ancient enemy may have met its match. The COVID-19 pandemic sucked so much air out of the news cycle that relatively few people noted the emergence of an amazing new malaria vaccine. The injection infects people with “live Plasmodium falciparum parasites, along with drugs to kill any parasites that reached the liver or bloodstream, where they can cause malaria symptoms.” According to Nature magazine, “the vaccination protected 87.5 percent of participants who were infected after three months with the same strain of parasite that was used in the inoculation, and 77.8 percent of those who were infected with a different strain.”

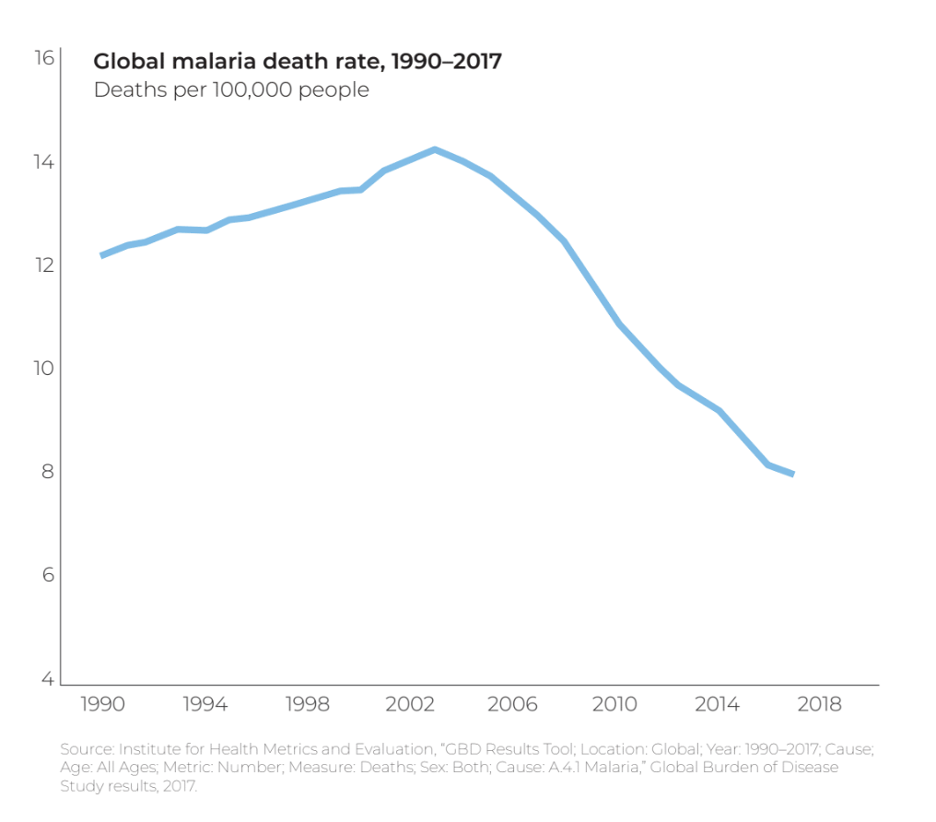

In our book, Ten Global Trends Every Smart Person Should Know: And Many Others You Will Find Interesting, Ronald Bailey and I noted that thanks to better treatments and preventive measures, the malaria death rate dropped from 12.6 per 100,000 in 1990 to 8.2 per 100,000 in 2017. That incremental progress is encouraging, but we very much look forward to the day when the malaria death rate stands at zero and the disease joins the other illnesses humanity has either extinguished or contained. Last year may have been a miserable one, but it appears to have delivered not one but two important vaccines. Surely that’s something for which we should be grateful.