Today marks the thirteenth installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

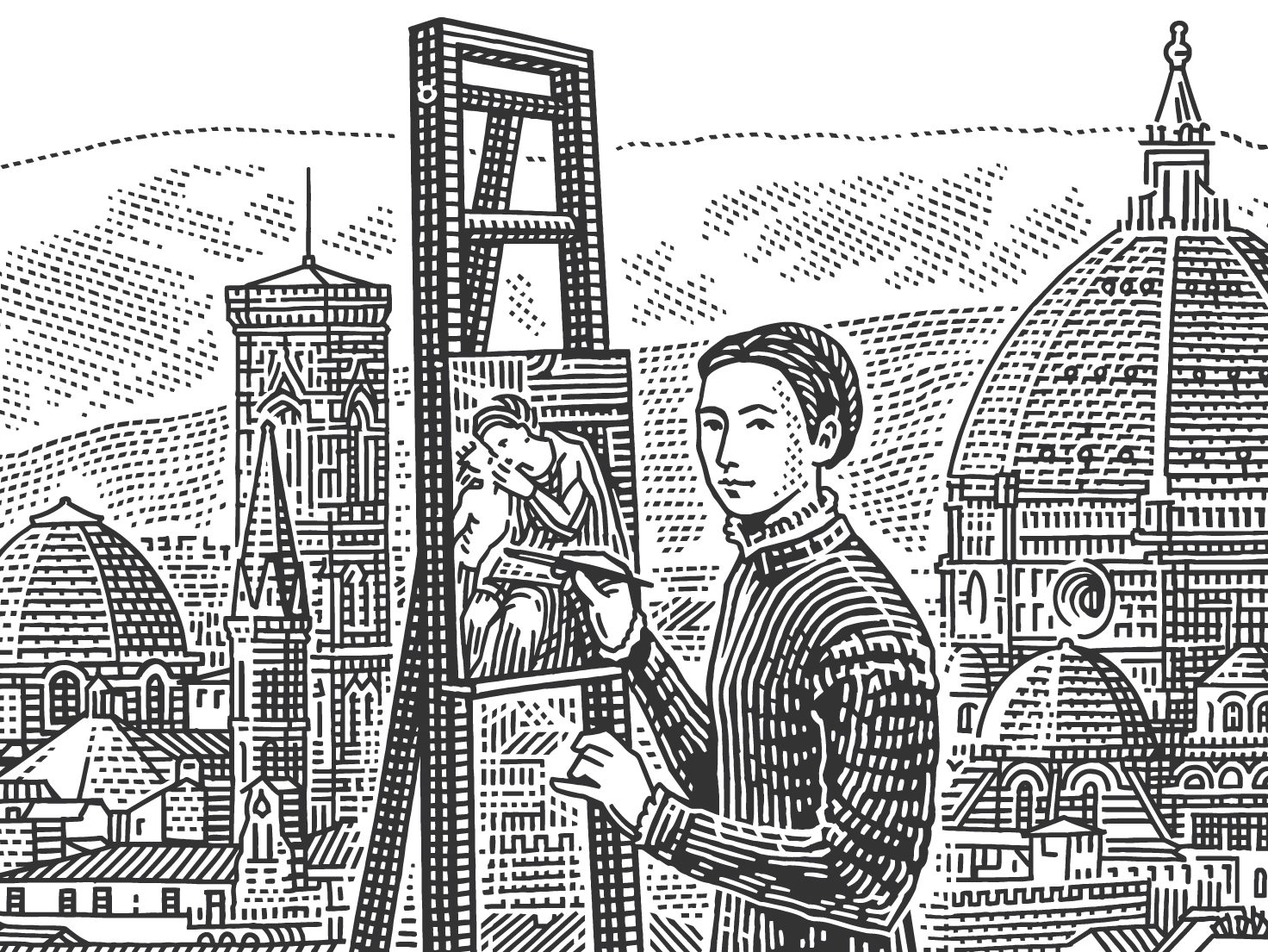

Perhaps no city so perfectly exemplifies the idea of progress as Florence during the Renaissance. Known as “the Jewel of the Italian Renaissance,” and sometimes, “the birthplace of the Renaissance,” Florence was at the heart of too many groundbreaking developments to mention. The city contributed to significant advances in politics, business, finance, engineering, science, philosophy, architecture, and—above all—artistic achievement. Florence produced historic art projects throughout the Italian Renaissance (1330–1550 AD), particularly during the 15th century, the city’s golden age. The Florentines’ wide-ranging contributions to human progress are all the more amazing when one considers that a pandemic killed half of the city’s population in the 14th century.

Today, Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany. Tuscany, known for its natural and architectural beauty, may be the most frequently photographed region in Italy. Florence is also Tuscany’s most populous city, with over 300,000 inhabitants and 1.5 million residents in its greater metropolitan area. With its long history and arresting scenery, Florence is a popular tourist destination that often merits a place on lists of the world’s most beautiful cities. The Historic Center of Florence is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Florence is also a key center of Italy’s fashion industry.

That is fitting because the story of Florence’s rise to prominence began with cloth. More precisely, woolen cloth. Tuscany has plenty of sheep and grazing land, and for centuries Florence produced wool locally. But around 1280 AD, Florentines began to import wool from England. English wool was of higher quality. Florence’s river, the Arno, made cleaning large amounts of imported wool achievable.

Florence enjoyed a central trade location between East and West. Some Florentine merchants realized that their city was perfectly situated to combine top-notch wool from England with the world’s best dyes from Asia—resulting in uniquely luxurious woolen cloth. The Florentine woolen fabric was soon in high demand throughout Europe. By the 14th century, one-third of Florence’s population worked in the woolen cloth industry.

Thus international trade set Florence on a path toward success in the fabric business. The city’s booming cloth industry created a large, wealthy merchant class. As the Florentines grew rich, new finance and banking innovations further elevated the city’s prosperity.

As Florence’s wealth increased, its people needed to exchange larger and larger amounts of florins (i.e., the city’s currency from 1252–1533 AD). Thus Florence became the first city in centuries to mass-produce gold coin currency. Florentine bankers soon became renowned experts at coin valuation, and the florin became the most trusted currency in Europe.

Moreover, Florence became the first city-state whose bankers charged interest on loans. Historically, most bankers throughout Europe would not charge interest because doing so was widely considered to be a sin called usury. However, giving out loans without charging interest is risky and usually unprofitable. As a result, for many years, Jews were among the only Europeans who could enter the money-lending business without going bankrupt. But Florence’s Christian bankers found a loophole with a bit of creative accountancy: they presented interest as a voluntary gift on the part of borrowers or as compensation for the risk taken on by lenders. (Those who failed to pay the technically voluntary fees were often blacklisted by Florence’s banks and unable to obtain future loans).

Charging interest let the Florentine bankers make credit widely available in a profitable and thus sustainable way. Not only did that put loans within reach of many Florentines, but Florence’s bankers soon became the money-lenders of choice for the wealthy and powerful throughout Europe, including royalty and the Pope. The bankers’ financial services also included facilitating trade by furnishing merchants with bills of exchange that allowed them to pay off their debts while in a different town from their creditors—a concept familiar to anyone who has ever mailed a modern check. Florence’s banks accomplished that by opening offices or branches in various cities. Florentine bankers also perfected double-entry bookkeeping.

Through its lucrative cloth trade and innovative banking industry, Florence quickly rose to become the wealthiest city in Europe during the Renaissance. That wealth improved the lives of everyday people throughout the city. For example, Florence became the first city in Europe to pave its streets in 1339 AD.

The city’s wealth resulted in more than improving material conditions—it also prompted a shift in the way people thought. Humanism and classicism came into vogue. Humanism was an intellectual movement focused on human achievement and the enjoyment of life’s pleasures, such as beautiful gardens and art. Humanism contrasted starkly with the prior widely-held belief in asceticism. Florence’s growing upper and middle class increasingly engaged in intellectual pursuits, such as studying history and classical Roman texts, which allowed the former to recover lost knowledge in many fields. It is fitting that the literal meaning of Renaissance is “rebirth.” For example, by studying old Roman writings, the artist Raphael (1483–1520 AD) managed to recreate a rare blue paint pigment invented by ancient Egyptians.

Florentines considered their city to be the “New Rome.” That was partly because they brought back into practice much of the knowledge of the ancient Romans that had fallen into disuse. Like the ancient Romans, the Renaissance Florentines also felt that their home embodied an ideal city-state republic, guaranteeing individual freedom and the right to political participation to a portion of the population. Although, like republican Rome, Florence was not a true democracy but an oligarchy. The republic was also infamous for political intrigue.

Florence’s relatively inclusive political system, classicist appetite for knowledge, humanist zest for life, and the freedom afforded by growing prosperity all combined to give rise to the ideal of the “Renaissance Man.” Many Florentine men strived to attain far-ranging expertise across fields such as art, literature, history, philosophy, theology, natural science, and law. The educator Pietro Paolo Vergerio (circa 1369–1444 AD), who studied in Florence among other cities, wrote the era’s most influential educational treatise. That treatise, “On the Manners of a Gentleman and Liberal Studies,” published in 1402 AD or 1403 AD, helped to create the concept of a well-rounded liberal arts education.

Florence was the first Italian city-state to host a center for learning—the University of Florence—established in 1321 AD and relocated to nearby Pisa in 1473 AD. The scholar Giovanni Boccaccio, today best remembered for authoring the Decameron (a collection of stories also collectively known as l’Umana commedia or “the Human Comedy”), helped make the university into an early capital of Renaissance humanism. Together with the scholar Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374 AD), whose rediscovery of Cicero’s letters is sometimes credited as starting the Italian Renaissance, Bocaccio popularized writing in the vernacular rather than in Latin. Florence’s greatest poet, Dante Alighieri (circa 1265–1321 AD), authored his narrative poem, the Divine Comedy—which is still widely called the greatest Italian literary work—in the vernacular. That work was so popular throughout Italy that it helped establish the local Tuscan dialect as the default, standardized version of Italian, replacing other regional dialects.

While taught less than men, Renaissance women from wealthy families were educated in the classics and sometimes the arts. A notable example was Sofonisba Anguissola (circa 1535–1625 AD), an Italian noblewoman who studied painting under the acclaimed artist Michelangelo (1475–1564 AD). Although he spent most of his life in Rome, Michelangelo considered himself a Florentine (he worked in Florence in his youth). Anguissola attained professional success, and became the official court painter to the king of Spain. Her achievements paved the way for other European women to pursue serious artistic careers.

Florence’s rise was not without difficulties. In the 1300s, the Bubonic Plague pandemic swept through Italy. By 1348, the pandemic had reached Italy’s interior, including Florence, and revisited the city in periodic bouts. The illness is estimated to have killed approximately half of Florence’s population. Such a widespread loss of life created intense economic and social disruption. Yet even in the aftermath of that tragedy, Florence continued to innovate and create. By the 15th century, the city had entered its golden age. The citizens poured their fortunes into patronage of the arts, and the Catholic Church also paid for many artistic projects. Pope Julius II (1443–1513 AD), in particular, was known for artistic patronage. Florence’s wealthiest banking family, the Medicis, also became famous for financially supporting Renaissance artists.

Florence was teeming with geniuses. If you could take a stroll through the city in the 15th century AD, you might run into the polymath Leonardo Da Vinci (1452–1519 AD). Born and raised in Florence, Da Vinci was the quintessential Renaissance Man, whose notebooks spanned topics ranging from anatomy to cartography and painting to paleontology. Or you might meet the artist mentioned earlier, Raphael, considered one of the three great masters of the Renaissance, together with Da Vinci and Michelangelo. You might greet the sculptor Donatello (1386–1466 AD). You might encounter a young Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527 AD), who worked as an official in the Florentine Republic, wrote the famous treatise The Prince and is often labeled the father of modern political philosophy and political science. You might chance upon the explorer and merchant Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512 AD), from whom the Americas get their name. You might pass by the art workshop run by the artist and businessman Andrea del Verrocchio (1435–1488 AD), who mentored many of the city’s best artists, including Da Vinci. Verrocchio’s workshop also helped cultivate Florence’s atmosphere of competition in the development of new artistic techniques. You might cross paths with Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446 AD), often called the first modern engineer and the father of Renaissance architecture, who designed Florence’s iconic cathedral. Or perhaps you would happen upon Sandro Botticelli (circa 1445–1510 AD), yet another Florentine artistic legend.

Whereas European art had degraded during the Dark and Middle Ages to simple cartoonish figures, the Renaissance not only resurrected the hyper-realistic and proportional sculpture style of the ancient Greeks and Romans but went further in developing extraordinarily sophisticated painting techniques.

Florentine artists perfected proportionality and foreshortening (shortening lines to create the illusion of depth). Moreover, they developed the so-called canonical “four techniques” of the Italian Renaissance: cangiante, chiaroscuro, sfumato, and unione. Sfumato is a way of subtly blurring outlines to give the illusion of three-dimensionality. Chiaroscuro is a method of contrasting light and dark paint to convey a sense of depth. Cangiante creates the illusion of shadows using a limited color palette, and unione is a color transition technique that produces dramatic effects.

In sum, the Florentine artists’ processes and techniques established the basis of traditional Western painting, with their methods still in use after hundreds of years.

Florentines produced many of history’s most acclaimed paintings and other artworks. Those include The Birth of Venus, Primavera and Venus and Mars by Botticelli; the sculpture David and the artworks of St. Peter’s Basilica and the Sistine Chapel such as the Creation of Adam by Michelangelo; The School of Athens (mentioned in our seventh Centers of Progress installment) by Raphael; and The Last Supper and The Virgin of the Rocks by Da Vinci.

The Mona Lisa—an early 16th-century portrait by Da Vinci depicting a Florentine merchant’s wife—is today the world’s most-visited painting. Situated in the Louvre museum, it attracts around 8 million of the museum’s 10 million annual visitors.

Not everyone was happy with Florence’s prosperity and artistic creations. Progress is seldom without controversy. An anti-humanist, pro-ascetic backlash led by the radical friar Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498 AD) briefly threw Florence into turmoil. Savonarola encouraged his followers to destroy paintings, musical instruments, fine clothes, jewelry, humanist books (such as the works of Boccaccio), and other allegedly sinful possessions. Mass burnings of such objects were called “bonfires of the vanities.” Savonarola’s movement, sometimes considered a precursor to the Protestant Reformation, eventually got him excommunicated by the Pope and executed by political opponents. The burning of Florence’s so-called vanities ceased, and many of the city’s artistic masterpieces survive to this day.

Innovations in trade, business, and banking helped make Florence wealthy, and the Florentines spent enormous sums toward the patronage of artists. As the writer Eric Weiner noted, “Genius is expensive.” The city’s merchants and bankers were as key to Florence’s flourishing as the artists they funded. In turn, those artists conducted extraordinary experiments in creativity and produced some of the world’s most remarkable artistic accomplishments. The powerhouse of the Renaissance, Florence not only revived lost knowledge from Greco-Roman texts but revolutionized art in a way that would come to define Western painting. Florence is also a symbol of resilience in the face of a pandemic. For these reasons, Renaissance Florence undoubtedly deserves to be our thirteenth Center of Progress.