Today marks the 33rd installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 32nd part of this series here.

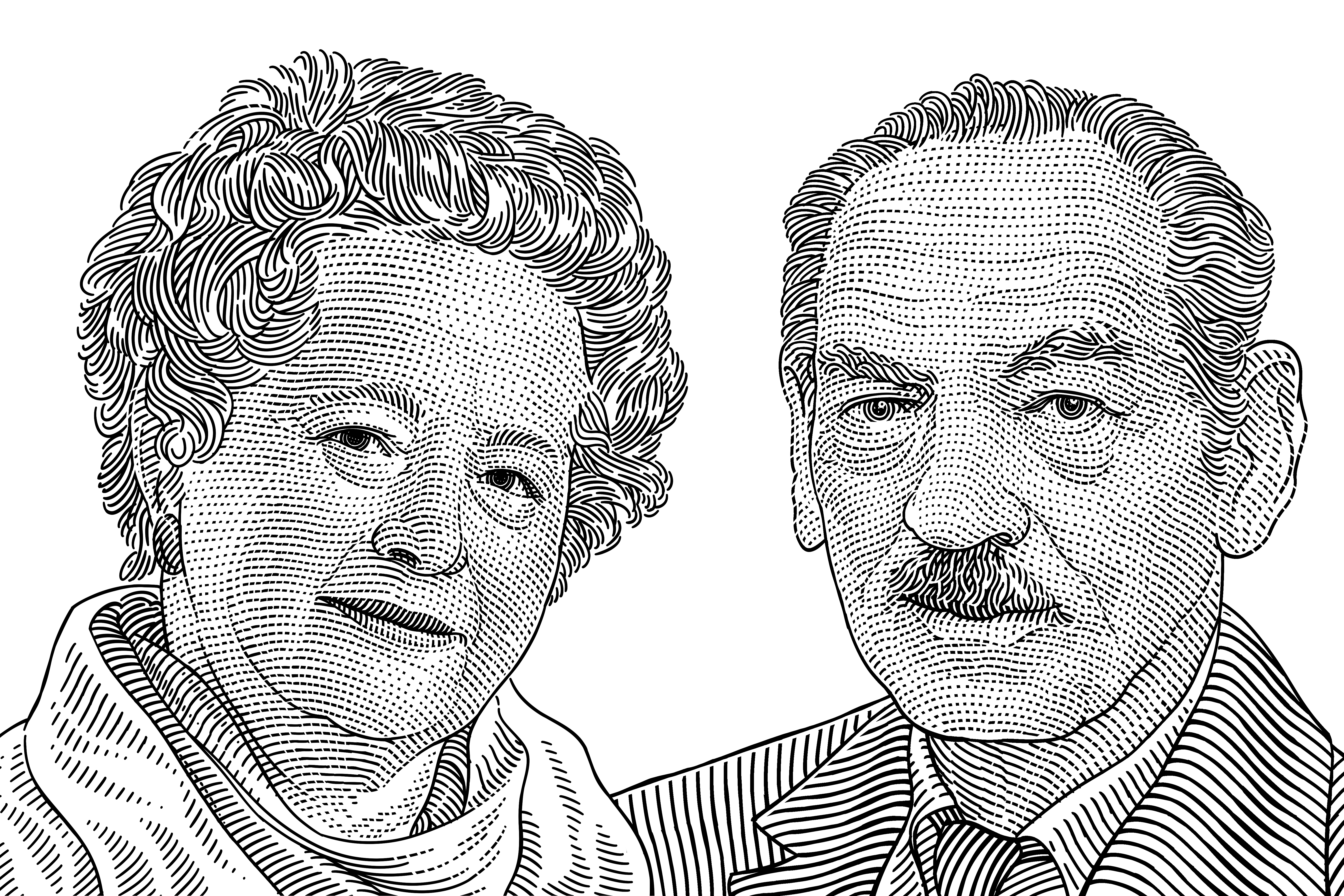

This week our heroes are George Hitchings and Gertrude Elion, two American scientists who pioneered the development of rational drug design. For most of history, the traditional method of drug discovery relied on a trial-and-error approach to determine the effectiveness of different treatments. Contrary to perceived wisdom, Hitchings and Elion’s new method of rational drug design focused on studying the differences between human cells and disease-causing pathogenic cells. From these findings, the method develops specifically-designed drugs to only target harmful pathogens.

Hitchings and Elion’s rational drug design technique has changed the way many new drugs are created, and their method has led to the creation of drugs to fight leukemia, malaria, gout, organ transplant rejection, and rheumatoid arthritis, just to name a few.

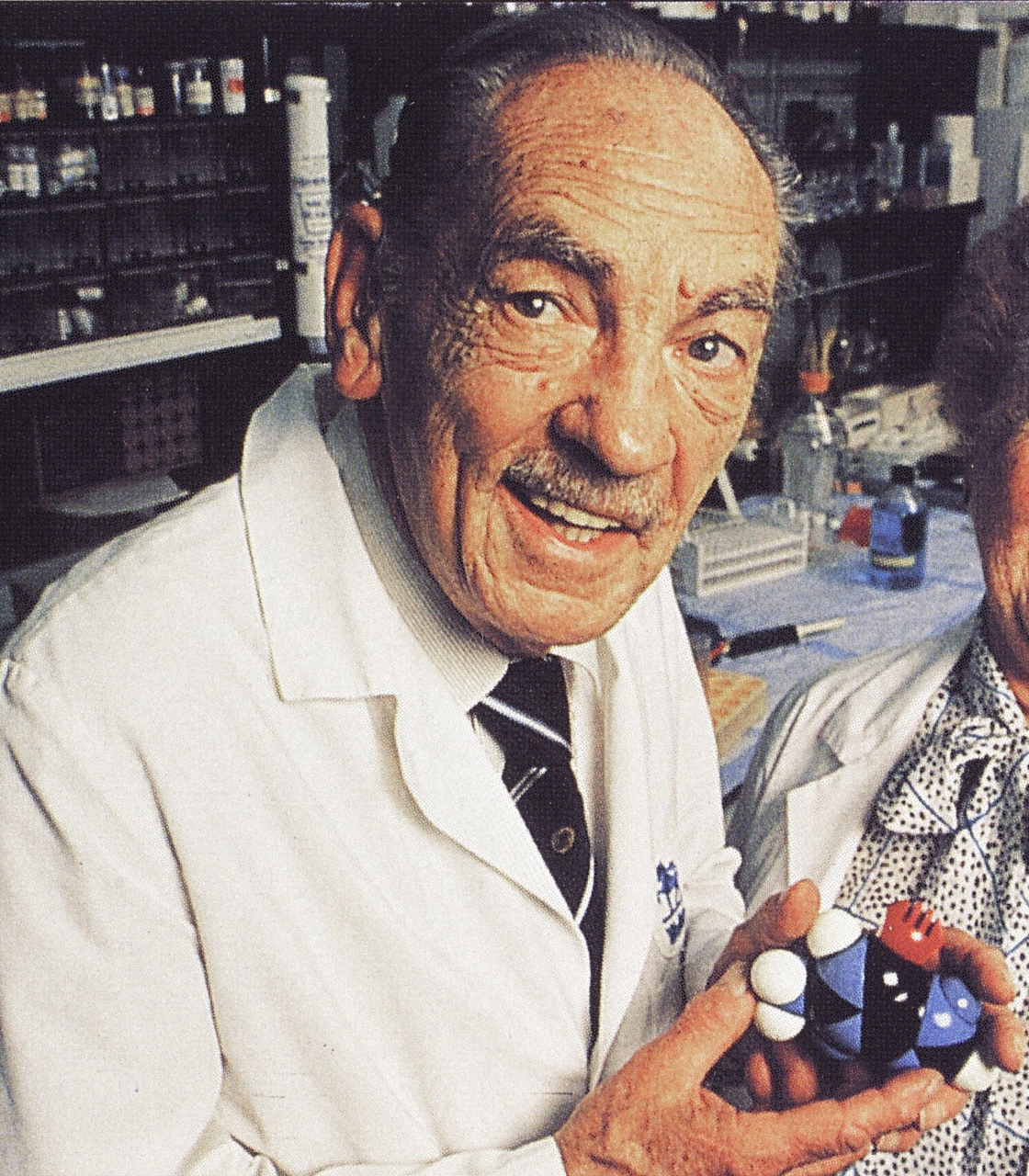

George Hitchings was born on April 18, 1905 in Hoquiam, Washington. When Hitchings was just 12 years old, his father died from a prolonged illness and Hitchings later noted that the impact of his father’s death made him want to pursue a career in medicine.

Hitchings graduated from Franklin High School in Seattle in 1923. That same year, he enrolled at the University of Washington to study chemistry. After graduating cum laude in 1927, Hitchings stayed at the University of Washington and obtained his master’s degree in 1928. Hitchings then moved to Harvard University as a teaching fellow and received his PhD in biochemistry in 1933.

Over the next decade Hitchings held several temporary appointments at different institutions. As he later admitted, his career “really began in 1942,” when he joined Wellcome Research Laboratories (now part of GlaxoSmithKline) as Head of the Biochemistry Department. Two years later, Hitchings wanted to hire a research assistant and that is where Gertrude Elion enters our story.

Gertrude Elion was born on January 23, 1918, in New York City. Elion was a bright student, who graduated from high school at just 15 years old. She later enrolled at Hunter College on a full academic scholarship. When Elion was 15 years old, her grandfather died of cancer. Similarly to Hitchings, the death of a loved one led to Elion’s lifelong commitment to a career in medicine.

After graduating from Hunter College with a degree in chemistry in 1937, Elion ran into what she described as a “brick wall.” The Great Depression made jobs very difficult to come by and women looking for jobs in science faced still greater obstacles. Elion later reflected that in the 1930s, few employers took her seriously. After attending job interviews for roles that she was qualified for, interviewers would often say she would be “a distraction” in a lab full of men.

After being rejected by numerous employers and graduate programs, she accepted an unpaid position as a laboratory assistant to a chemist. In 1939, Elion enrolled in a master’s program studying chemistry at New York University. Elion worked as a high school teacher throughout her master’s studies and obtained her M.Sc. in 1941.

In the early 1940s, with many men in the military, new doors opened for women in the sciences. After working as an analytical chemist for a food company, Elion became bored with her work. After a six-month stint in a lab run by Johnson and Johnson, she was hired by Hitchings as his research assistant in 1944.

Hitchings had thought that there must be a more rational approach to drug discovery than the existing trial-and-error method. The pair developed a method of drug design that focused on determining the differences in biochemistry and metabolism between human cells and the disease-causing pathogens. The pair could then design specific chemicals that could kill or inhibit the reproduction of harmful pathogens, without having to harm any healthy human cells.

Using their rational drug design method, Hitchings and Elion successfully developed drugs that are used to treat a variety of different conditions, including leukemia, gout, malaria, meningitis and viral herpes– just to name a few. Researchers around the world quickly copied Elion and Hitchings’s approach to drug design. Within a few years, scientists using the rational drug design method had created medicines to fight the viruses that cause cold sores, chickenpox and shingles. Eventually, they developed azidothymidine (AZT)– the first treatment available for HIV/AIDS.

Elion later wrote, “when we began to see the results of our efforts in the form of new drugs which filled real medical needs and benefited patients in very visible ways, our feeling of reward was immeasurable.”

Later in her career, Elion taught at Duke University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In 1967, when Hitchings became vice president in charge of research at Burroughs-Wellcome, Elion succeeded Hitchings in his old job.

In 1976, Hitchings became Scientist Emeritus at Burroughs-Wellcome. He also served as an Adjunct Professor at Duke University between 1970 and 1985. Elion officially retired in 1983, but like Hitchings, she remained working in the laboratory on a part-time basis as Scientist Emeritus.

Throughout their lives, Hitchings and Elion received dozens of awards and honors. Most notably, they received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1988– an award which they shared with Sir James Black, a Scottish pharmacologist. In 1974, Hitchings became a member of the medicinal Chemistry Hall of Fame and a Foreign Member of the Royal Society.

In 1991, Elion received the National Medal of Science from President George H. W. Bush. That same year, she became the first woman inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for her important work developing a drug called 6-mercaptopurine, which offered new hope in the fight against leukemia. Like Hitchings, Elion also became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 1995. While Elion never received a formal PhD, she was awarded an honorary PhD from Polytechnic University of New York in 1989 and an honorary S.D. degree from Harvard University in 1998.

Hitchings died at the age of 92 in 1998. Elion passed away the following year, aged 81.

The work of Elion and Hitchings fundamentally transformed the conventional trial-and-error method of drug discovery. Their rational drug design method has been used to create dozens of different treatments for an array of life-threatening illnesses. Rational drug design has already saved or prolonged untold millions of lives– a number that will only increase as more drug treatments are developed. For that reason, George Hitchings and Gertrude Elion are our 33rd Heroes of Progress.